Wednesday, December 15, 2010

I've Moved

And so, over at The Museum Game, I'm trying to post frequently about the things that make an impression on me and that make me wonder--not just during museum visits but during each day. Sometimes it'll be a quotation from what I'm reading. Sometimes it'll be a response to what I've seen in the news. Other times, it might be something I've caught sight of as I'm driving by. Come check it out.

Thursday, August 26, 2010

The Found Art of Getting Lost in an e-Book

The pros and cons of e-books have been enumerated and discussed frequently enough in the press lately that anyone who thinks reading is on the decline in this country (former NEA chairman Dana Gioia among them) should think again. Unless it turns out that all we ever read are reviews of e-readers.

But here's one thing that I haven't seen anyone writing about when they talk about the relative merits or frustrations of an iPad, a Kindle, or a nook: the way that some of these devices let you truly lose yourself in a book. And I mean lose your place, lose where you are in the story.

Last night, I was reading Simon Mawer's 2002 novel The Fall, on an iPad, using the Kindle app. With the Kindle app, all you see are the words on the page, plus the title of the book at the top. If you tap on the screen, you'll get a variety of menu-type buttons to appear, including the mysterious Kindle-speak marker that tells you where you are in the book. No page numbers, just "Location 6417-6429", in my case, and "97%". Apparently, when I left off last night, I was close to finishing the book. But I'd been reading for a while, and hadn't tapped the screen so I could see these buttons. Which meant that, as I was reading, I had lost track of how much more there was to go in the story.

If I'd been reading a print book, I'd have seen and felt, constantly, the thickness of the remaining pages in my right hand. Holding and reading a physical book, the reader is always aware of where he or she sits in the overall arc of the story. That knowledge is, I'd argue, part of the reading process. As children, we learn the shapes of various stories, and as older readers, we have that sense of the narrative arc hard-wired into our brains. But I think we cheat. We look at how much more there is in the book and that tells us whether what we're experiencing is the denouement or some other preliminary resolution that may well be challenged again before the story's done. We do the same thing with television and movies. If it feels as though something is winding down, we might glance up at the face of the dvd player, or glance at our watch, to double check. (This works will all movies, except the final Lord of the Rings film, which came to an end three or four different times.)

With print books, we process the story itself in some sort of combination with the physical knowledge of the shape of the book. With an e-book system like the Kindle or its app, we can't do that. I'd suggest that it's this lack of page numbers, lack of pages altogether, lack of markers that makes reading on an e-book (some e-books) a radically different way of processing a narrative.

Could I have cheated with the iPad/Kindle? Sure. I could have tapped the screen at any time to see what my percentage was. And indeed, when I first began reading The Fall, I did that fairly frequently, out of excitement to see how quickly I was moving through the story. But here's the thing: as I became immersed in Mawer's book, I forgot to check. I just read, with no sense at all of where the book would take me and when we would get there. I was completely at sea in a way that I would never have been with a physical book.

[A note to iBooks users: Apple's e-book interface does its best to make the experience feel as though you're reading a real book (there are page numbers, the title, and a trompe l'oeil book cover), but it gets one thing wrong: the clock is always visible. You can never lose track of time when reading something from the iBooks store.]

My new policy? I'll try to resist the temptation to check my progress in an e-book. I want to see how well I can do in predicting when a book is ending, without being able to turn that last page.

Q: Do you cheat? Do you like to know where you are in an e-book?

Monday, August 16, 2010

Laces Tied

I took two weeks off from rowing recently. Coming back to the river today for the first time, my technique was a bit rusty, my hands a bit tender, having lost almost all of their hard-earned calluses. Still, everything was familiar, as it would be after fifteen years at this sport. But I did notice the language we rowers use to communicate about our sport. It’s not the kind of stuff you get to say around the house, the office, or the grocery store. “Weigh enough.” “Hold water.” Huh?

A few years ago, I wrote something up to explain why I cherish these strange words, and why it would never occur to me not to use them, if I had the choice. Here’s that piece, dated by the ages of the children, but still true in many ways.

“Let’s have Laces Tied at 3:00. And Ball Kicked at 3:15.” This is my son the soccer player, sixteen years old and a wise guy, mocking the language of his mother’s sport. “‘Hands On!’” he scoffs. “Why can’t you just say ‘Get the boat’?” I try to explain it to him—the need for choreographed movement, the need for economy—but he brings his father into the game, and now there are two of them doing a call and response of phony rowing commands as we get ready for dinner. “Let’s have Table Set. In Two,” my son says, capturing the coxswain’s beat. “And Forks Raised at 7:00,” adds his father. My daughter mercifully, being thirteen, refuses to join in.

Once we sit down, I take up the challenge again, and try to convey to my resistant family the necessity of using such language in rowing. Of course, isn’t it obvious? That a coxswain who needs her crew to act quickly would rather say “Weigh ‘nough” than “Everybody stop now”? Or that the same cox, perhaps just as breathless with excitement as her crew is with effort, will choose to say “Up two in two” instead of the much sillier “In two strokes, we’ll take the rate up by two strokes per minute”? My family grants me this, though they balk at “weigh enough” which, for them, conjures up images of Admiral Nelson. Their objection lies, most of all, with “Hands On”. There is no need for such a phrase, they argue—no need for such economy or specificity when everyone’s standing by the boat rack or talking on the phone about the plan for race day.

And on one level they’re right. As long as the coxswain bellows loud and clear, the crew will understand that they have to get their hands on the boat and prepare to move it out of the rack. But there is more to it than that, and I lose the thread of the dinner conversation as I prepare a more thorough response. Economy makes rowers adopt this abbreviated language, but beauty makes us hold onto it and use it even when we could get away with what my family would call normal speech. Not the beauty of the words themselves, but the grace of the movements that the words call into being. I am not a military-minded person, nor have I ever worked on an assembly line. But on my very first day at a boathouse, I was seduced by the litany of phrases punched out in rhythm, and the rowers’ synchronized response to these commands. As a novice, I couldn’t yet feel the swing of the boat, but I could already participate in the elegance of the sport by reaching for the gunwales in unison with everyone else, in a perfectly choreographed lift.

Maybe I don’t have to tell my rowing partner “We’ll have hands on” at a certain time. Maybe I could just say “Let’s be ready to go.” After all, that’s what my son’s soccer coach says, and the players all know exactly what he means. But I can’t help it. The speech patterns of rowing, with their unique cadence and lilt, are too much a part of the sport for me to let them go. Here in the Northeast, we spend enough time off the water as it is. Why not bring the poetry of rowing into our lives whenever we can, even if we don’t need to?

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Dateline: Paris (Movie Title edition)

First, Leap Year. A nothing of a film (not great, not offensive either), with a clever premise, as these things go, about a young woman who sees her chance to make a wedding happen by proposing to her boyfriend on February 29th. Apparently, in the wacky world of the movie, a woman can only do this in Ireland and only on that day. God forbid that she could be so bold on any other day, in any other place.

I don't know what the French for "leap year" is, but it must not be evocative enough. The French title is: "Donne-moi ta main." Give Me Your Hand. Is it possible that in French even an imperative command can sound romantic? Am I missing something?

And then we have a translation of a translation. Stieg Larsson's second book in the Millennium trilogy was originally called "Flickan som lekte med elden," which translates to its English title: The Girl Who Played With Fire. The second movie is out in the US with that same title. In France, though, an attempt to be literal turns into this clunker: "Millennium 2: La fille qui revait d'un bidon d'essence et d'une allumette". Just trips off the tongue, doesn't it? The Girl Who Dreamed of a Can of Gas and a Lighter.

So the next time I roll my eyes at the English translation of some foreign film (snob that I am), I'll have to remember that it goes both ways.

Q: Any movie-title howlers you'd like to share?

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Dateline: Ljubljana

I just spent four days in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, because of a book. It goes like this: Some time in the late eighties I read an article by Robert D. Kaplan about the break-up of Yugoslavia. When his book Balkan Ghosts came out, I snapped it up. When my son was about twelve and a precocious reader, I gave him his own copy. He couldn't get enough. Born the year the Berlin Wall fell, spending time nearly each summer in the Balkan part of Greece where my family's roots are, and growing up with newspapers full of Slavic names and datelines in small Balkan villages where events of enormity took place, he almost had no choice but to be fascinated by Kaplan's book.

Fast forward to college and his decision on where to study abroad. Still the Balkans, always the Balkans, with Kaplan's flame alive in his thinking. And so, for the skiing: Slovenia. Now I've been there for the second time in two years--and all because of a book.

There are many interesting things about Slovenia, this tiny country with a passel of alps, turreted churches, just enough coastline to hold a town that dates to the Venetians, and an entire population seemingly on wheels (either bicycles or rollerblades).

And about that population: two million. If there are only two million of you, you all learn English.

I don't know any of the great names in Slovene literature. But I do wonder what will happen to that tradition if, as seems to be the trend, no one outside Slovenia bothers to learn Slovene anymore. Even vigorous translation programs might not be enough to stem the tide of evaporation.

And here I am, worrying about Slovenia because of a book I read (and re-read) and admired.

Q: Have you ever made a major to medium-sized life choice because of one specific book? OK, even a small life choice?

Monday, May 17, 2010

Movie Review: Iron Man 2

Is it a good thing or a bad thing to go with your daughter to see Iron Man 2 on Mother’s Day? The answer isn’t entirely clear. On its most obvious level, Iron Man 2 is a 13-year-old boy’s dream: weapons, explosions, and Scarlett Johansson. But at the same time, this is a movie that not only puts Robert Downey Jr. on screen in nicely tailored suits, but also musses up his hair from time to time and shows us plenty of close-ups of the big brown eyes. Who’s happy now? And let’s not forget that the almost-pointless plot offers us Gwyneth Paltrow as the CEO of an arms manufacturer. Glass ceiling, indeed.

Still, the movie begins with a striptease, albeit not your typical striptease. This striptease takes the Iron Man suit apart, to reveal RDJ fully clothed. Behind him, women dance around in Sexy Cheerleader costumes while fireworks explode. Yup, the man is the attraction, but he’s clearly the one in charge of the display, and he has no intention of taking his suit off.

Iron Man 2 is not exactly the most coherent of films, and perhaps that’s what makes it so entertaining. The actual plot is there only as a sort of pictorial background. The real interest in the movie is all the rest of it—the banter between Paltrow’s Pepper Potts and RDJ’s Tony Stark, the earnest and goofy robots, Jon Favreau bumbling his way through a nebbishy anti-director’s role, and Mickey Rourke reprising his Wrestler style, but looking somehow both disgusting and endearing at the same time. All of this is the filigree that decorates the plot about the Bad Guy who wants to Blow Things Up. It’s the icing on the Iron Man beefcake.

Among the many things that Iron Man 2 is is a riff on George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara. Think about it. Shaw gives us an arms manufacturer who believes that his work brings and keeps peace. The play avoids being a diatribe against war and weapons by both terrifying its audience with a grim vision of destruction as well as the hopefulness of the arms-maker’s vision. In the hands of skilled actors (like Simon Russell Beale who led the cast in London two springs ago), it’s an unsettling exploration of violence and creation.

Iron Man 2 doesn’t exactly unsettle, but it does raise the specter of an army of drones succeeding at something humans don’t want to do, and don’t always want to be good at. The movie serves, like it or not, as a position paper against drone use, endorsing an old-fashioned view of warfare as hand-to-hand (or electrified whip-to-iron hand) combat. Tony Stark in his red-and-gold suit, and Don Cheadle in his silver one, are far nobler creatures than the drones whose heads and faces have been replaced with guns by Mickey Rourke’s Ivan Vanko.

But in the end, it’s not the Cold-War replay we’ll be thinking about when we leave the theater. Nor the movie’s staging of the current drone warfare issue. We’ll be thinking about how RDJ talks to the robots, and about the preposterousness of Sam Rockwell’s excellent slime-ball. And about the grace with which Downey stretches, bats, or swats away the electronic images that seem to be an extension of his imagination.

Wednesday, May 5, 2010

The Story Catcher

For a writer, I’ve been acting a little strange lately. I’ve been driving around eastern Massachusetts with a pre-amp and a pop screen and other assorted pieces of sound equipment in a large messenger bag, and wielding a folded-up microphone stand in one hand. I’ve been poring over sound files, cutting out extra-long pauses and noticing that I’m starting to recognize the shape that particular words form in the sound waves of Garageband. I’ve been working with short fiction, making editing suggestions, commenting on tone. But none of it has involved looking at actual words.

This past Saturday marked the launch date for my new writing venture: The Drum, A Literary Magazine For Your Ears. The Drum is a lot like other online lit mags, except for one thing: the stories, novel excerpts, and essays it publishes exist only as sound files. This is writing out loud. Literature to listen to.

I had the idea for The Drum some time over the summer, as I listened to audiobooks during long car drives and wondered why there couldn’t be an audio counterpart for short works. I did some research and, at that point, didn’t find anybody who was doing exactly that. I took the fateful step of mentioning my idea to two friends (whose names appear on The Drum’s masthead) who rather than pat me on the arm and change the subject, reacted with enthusiasm and—more dangerously—with names of people I should talk to to make the idea happen. Over the next several months, and with help from lots of people, I gradually put together the magazine whose website will go live on Saturday.

The process has been fascinating. I have learned that, thanks to the truth of six degrees of separation, you already know everyone you need to know to get practically everything done. A lawyer to draft the rights agreements? The mother of my daughter’s castmate knew just the right person. A web-builder? My rowing coach referred me. A logo designer? Two rowing connections led to that one. How to incorporate and apply for 501(c)3 status? A rowing/hockey double-whammy. Sound editing? My neighbor’s son. All fall, I turned all my friends, writers or not, into focus groups for one aspect of the magazine or another. There was no coffee-drinking or hockey practice or dinner that didn’t involve some sort of brain-picking on my part, if only for a moment. (Perhaps the biggest lesson here was: if you want to get something done, ask a rower.)

But despite all the real excitement I’ve felt at getting the project ready, the best part has come these past two weeks, as I’ve begun the actual recording—when the solitude of writing turns collaborative. Grub Street very kindly allowed me to use their space as a central recording location. But that didn’t cover writers like Aimee Loiselle who lives in western Massachusetts. To save her a long drive, I recorded her short story in her friends’ farmhouse midway between our two homes. Last week alone, I recorded in a Back Bay apartment, the Park Plaza hotel, and homes in Franklin, Oxford, and Jamaica Plain. There have been slight occupational hazards, like the train rumble in Porter Square, the dog barking in Annisquam, and another dog chewing loudly on a bone on Commonwealth Ave. All of it, wonderfully, can be edited away.

As I go from house to apartment to office, I joke that I’m the Story Catcher. But it’s kind of true. I go around capturing the American Short Story in its element, like a cross between a lepidopterist Nabokov and the legendary Alan Lomax, who recorded folk music throughout the US in the 30s and 40s. My travels are a vivid reminder that there are stories everywhere, and there are great writers everywhere, eager to hear their words brought to life. To me, the short works to be published in The Drum are the records of a new American folklore—the folklore of contemporary literary culture.

So last Saturday, again thanks to Grub Street, The Drum made its debut at Grub’s Muse and the Marketplace conference. I was busy capturing stories all day both days. Seven of the Muse panelists contributed recordings during their free sessions, and a dozen other Muse participants came to the The Drum's walk-in sessions to record their 500-word pieces of flash fiction that we might include in a future issue. (If The Drum doesn’t take the piece, you get to keep the sound file as a souvenir.) If you missed the Muse, come by the website and hear the first batch of writers aloud at The Drum.

[this post first appeared on Beyond The Margins]

Friday, April 16, 2010

From the Mixed-Up Files to the Midnight Library

My favorite children’s book led me to break the law. Well, not a real law. A college law. The law that when the library closes, you need to leave the premises, not hide away in the basement with a sleeping bag and a stash of food, so you can spend the night wandering the wood-paneled reference room with is club chairs and balconies. The children’s book that sent me onto this crooked path? From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, of course.

E.L. Konigsberg’s 1968 Newberry Award-winner about a brother and sister who solve a mystery while hiding out in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art captivated me right away. As a child whose upbringing was often confusing and usually chaotic, I loved Claudia and Jamie’s ability to read meaning into the clues they discovered. Their world was a mystery they could solve. And their world was a world of their own making, a home fashioned out of a public place; a public place turned private, safe, and even cozy. Of course I’m sure I didn’t realize all of this at the time. Reading and re-reading the book in childhood, I only knew that I loved the way the children wandered among the artworks at night, how they fished coins out of the museum fountains to spend in the vending machines, how they outsmarted not just the forger of the mystery plot but all the other adults who ran the museum or came and went in its exhibits during the day.

As a young adult, I knew that I wanted to experience that midnight ownership of a public place. I could have spent the night in the science center. The performing arts building would have been an even better choice, since it was the closest thing my small, liberal-arts college offered as a museum at the time. But, no. It had to be the library. The college library offered a perfect combination of 1. Opportunity for mischief and 2. Books. The library, and especially the reference room with its coveted windowed alcoves, was my favorite place on campus.

On the planned night, my college boyfriend and I carried fuller-than-usual knapsacks through the main doors, pulled homework out from beneath our overnight stuff, and settled in to work until the closing warning sounded. We moved to the basement stacks known as the Tombs until the staff had finished its sweep, and then, once the lights went out and the Exit signs provided the only glow throughout the building, we emerged.

The library was a lovely place for me during the day, but at night, in a flashlight’s beam, it became magical: the books at rest, their stories and information seeming almost to breathe deeply in the silence of the space, the shadows gliding over the shelves, the chairs, the balconies as time passed.

I realize how thoroughly geeky this sounds, and I make no apologies. I was engaged in a purely meta moment of the adoration of books. Inspired by a book, I recreated its adventure. Among books. It was perfect.

Have you ever recreated a scene or event from a favorite book?

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Sample, Mix, Allude: How to Handle Originality

I’ve been thinking about plagiarism lately. Not that I’m planning to commit it. It’s not like I’m hoarding quotations in some rooftop bunker and planning to unleash them in a spree of improper citations. It’s just that, as I listen to songs with bass lines borrowed from older hits, or watch movies with scenes structured to allude to classic films, or think about David Shields’ recent manifesto, I wonder about the limits of originality in our creative culture.

I’m a fuddy-duddy about this, I know. In fact, one of my last jobs in academia was informally titled Plagiarism Czar; certain students charged with academic dishonesty were sent to me for re-education. I would show them how to cite and how to achieve the combination of deference and individual assertion that defines the American approach to intellectual sources. Whether my students were bumblers or connivers, I always tried to convey the fact that citing your source properly actually makes you sound smarter than if you simply borrow without telling. You get to drop the name and sound like the intelligent guest at the cocktail party—while still touting your own idea. Originality with the sheen of tradition.

Friday, March 19, 2010

March Madness: The Movie vs. Book Smackdown

Why should basketball have all the fun? In honor of March Madness, here is the First Annual Movie vs. Book Smackdown Tournament. You decide who wins--the book or the movie version--and see which two works of art end up competing for all the marbles. You could end up with two books. You could end up with two movies. Or, in a genre-bending final, a book competing against a movie based on a different book!

This is just a small sampling of all the books that have acquired film aliases. It's a mix that offers two Jane Austens--one by Ang Lee and the other by Joe Wright--and two Joe Wrights, for that matter, with his Atonement possibly facing his Pride and Prejudice in the final. And there are two Keira Knightleys, thanks to Wright. The one, to me, obvious omission? W. Somerset Maugham, reportedly the author with the highest ever rate of book-to-movie adaptation among his works. The Painted Veil could have been in the Classics Division. Maybe next year.

Monday, March 15, 2010

Know Your Story: The Rector, The Waitress, and The Lion

On the refrigerator of the house we lived in in London more than a decade ago was a clipping from the “this day in history” section of The Independent:

1932: Harold Davidson, the rector of Stiffkey, is found guilty of disreputable association with women, after allegations that he made improper advances to a waitress in a Chinese restaurant. He died in 1937 after being mauled by a lion in Skegness.

I saved the clipping, thinking that though you can’t make this stuff up, I might try to make something out of it. For a long time, Harold Davidson’s sordid life was on my mental list of future writing projects. I toyed with possible plots and with various strategies for telling the story. Would it be an omniscient telling of the Rector’s, um, adventures? Would it be a post-modern tale (this was the 90s and I was on leave from a teaching job) embedded in some quirky frame narrative? Or would I use this poor man of the cloth as a vehicle for a commentary on patriarchy and imperialism (see above: 90s, teaching job)?

Thursday, February 25, 2010

See You Later: Writing in Two Languages

Some time in 1958 or 59, my parents moved into their first American home, an immaculate ranch in a suburb of Boston. The neighbors who came to greet them no doubt noticed my father’s excellent English and his strong Greek accent. My mother’s accent was harder to place, thanks to her mother who had thrown her own French Swiss into the Greek mix. What would have been crystal clear was that my parents were foreign. Not from here.

You can hardly blame the unsuspecting American neighbors for finishing their visit with a casual “See you later.” How were they to know that my parents would take this literally? That my parents would sit in their living room, dressed nicely, all the rest of the day, waiting for the promised return of their new friends?

I grew up with the story of “The See You Later.” It became not so much a phrase as a concept: seeyoulater. Or, with a Greek accent: σηγιουλεïτερ. For my parents, it began as a story of embarrassment, of a weakness unveiled despite their steady progress into American life. But when they retold it to me years later, The See You Later had already become a story of success. This, too, they had learned. They had faced this weird linguistic obstacle and they had triumphed. They would tell the story with a bit of a gleam in their eye. You can’t fool us, they said. We understand American idioms.

But the truth is that they never did understand English idioms. And neither did I. The cat that swallowed the pyjamas? Yup. Out of the clear? (In the clear, out of the blue, who’s to say?) Open my appetite? (Not if I’ve swallowed the pyjamas, I guess.)

Which brings me to my ongoing predicament as a writer—a predicament I’d like to think I share with other writers out there who make their creative way in a language that is not fundamentally their own. Writers who are Not From Here.

There are plenty of examples of bi-lingual or self-translating success. Nabokov and the Czech-born Tom Stoppard come immediately to mind. But I suspect most of us are a lot more bumbling than these two. Most of us have to constantly rescue our odd-sounding English with a last-minute realization that the syntax we used is borrowed from another tongue. Usually it’s during the exercise of reading a manuscript aloud when we catch the alien sound in time to correct it. But if we don’t hear it then, woe be to the readers and editors who have to deal (or choose not to) with the convoluted prose.

It took me a long time before I realized that I was frequently writing sentences in my head in Greek and then translating them into English. (My documented insistence on the past imperfect turns out to be me using Greek syntax in English.) Now that I know this is going on, the question is how can I and other bilingual writers make it an advantage?

1. A Built-in Thesaurus

If you can’t think of the right word in English, go to the foreign one and see if that sends you back to a more useful spot in English. The second language adds another layer of subtlety, a new dimension, and sometimes helps you find the better word.

2. An Editing Tool

If you know you have a tendency to write strange syntax, you can teach yourself how to look for those extra words—and you can learn to eliminate all extras, whether they come from self-translation or not. The end result is leaner, more efficient prose.

3. Attention to Diction

For those of us who don’t have English as our first language, it’s always going to be a tool rather than something instinctive. That makes us very aware of what we’re doing to screw it up, of course. But it can also, I hope, heighten our awareness of what a gift language is. Use it properly and it’s a powerful, wondrous thing.

Striving to Get it Right according to an English orthodoxy is just one way to handle the fact of bilingualism. It’s what worked for me, the kid who for a time was so desperate to blend in that she refused to speak English in Greece and Greek in America. (I still find it annoying when my mother throws the occasional English word into her Greek when a Greek one is readily available.)

For others, there is power in doing exactly the opposite of what I’ve described here.

If you’re a bilingual writer, what works for you? How have you drawn on the power of your other language? And what limitations have you found, as you try to formulate your literary style?

Monday, February 22, 2010

Greek Fiction: Is it European?

As often happens when I go into a bookstore, I emerge with more books than I planned to buy. Or with entirely different books than I planned to buy. Frequently, I go into a bookstore vowing that I will only scan the titles—the way you might take in familiar paintings in a museum—and not buy any more books until the pile on my nightstand, desk, dresser, windowseat (you get the picture) is read. I invariably fail.

Just last week, I went into my local independent to buy Aleksandar Hemon’s The Lazarus Project. I had read an essay by Hemon, or an article about him, several months ago and had been interested to find out more about his Balkan viewpoint. I ended up ordering a copy of The Lazarus Project, but did leave with another Hemon creation: his edition of Best European Fiction 2010, published by Dalkey Archive Press and with a preface by Zadie Smith. The boldly designed cover and the feel of the book in my hand were compelling enough. The content was, I felt confident, sure to intrigue.

I have yet to verify that assumption. But I do have a question. The table of contents is organized by country, beginning with Albania and ending with the United Kingdom. As a testament to the multiplicity of Europe’s nations—and perhaps a reminder that that whole Euro Zone thing might have been an idea against the cultural trend?—there are double entries from Spain, Ireland, and Belgium, covering the main languages spoken in those countries. There are three entries from the UK, recognizing the distinct literary aesthetics of England, Scotland, and Wales. The volume brings together between its yellow and black covers former foes and former countrymen, from within the former Yugoslavia and beyond. Interestingly, the cover manages to evade allusion to any national color scheme. Yellow and black evoke road signs more than anyone’s flag.

As for that question: Where is Greece? (Or the Czech Republic, for that matter, to balance out Slovakia?) Sure, we now know that Greece fudged the numbers to get into the Euro Zone, but I doubt Hemon was onto this information back when the book went to press. And even if you feel like kicking Greece out of the Union now, you have to admit that its geography puts it this side of Europe’s eastern edge.

I ask about Greece’s literary absence only in small part out of ethnic loyalty (as a first-generation Greek/American). I recognize that being the cradle of western civilization doesn’t give a country a lifetime pass on further achievements. If Greece wants to be included in a collection of European fiction in 2010, they should earn that spot.

So what was it that kept them from the roster? Was it a lack of good short work in 2009, leading up to publication? Or was it—as I almost suspect—something to do with the Greek narrative aesthetic and what I’ve found to be its reliance on broad melodrama?

Greeks whose taste in painting, design, architecture, and music I trust often recommend this novel or that as a book I must read in order to appreciate the merits of contemporary Greek literature. And I invariably find these books overwritten and obvious. They can’t hold a candle, in my view, to such writers as Venezis, Hatzis, Mirivillis, or Kazantzakis. These older writers—especially the first two—wrote with a surprising economy, finding their power in the inherently evocative nature of the Greek language. There was no need for over-writing, because they understood the strength of the tool they were using.

I confess to wondering if Hemon wasn’t right to leave Greece out at least for now. I cringe a bit at the thought that today’s Greek writers couldn’t make the cut, and I wonder if that's true.

If you're Greek, what's your thought on contemporary Greek fiction? Greek or not: is there such a thing as a national literary aesthetic?

Monday, February 15, 2010

Movie Review: Percy Jackson

There are many sad things in this movie, none of them intentional. The camerawork—which seems to consist of switching the camera on and off. The screenplay—which reduces Catherine Keener to wooden declarations of single-mom platitudes. The quirks, shall we say, of the story—which involves the quickest meet-cute trajectory ever recorded on film.

It’s not all a disaster, though. When Charon does take you to the Underworld, you get to see the brilliant comedian Steve Coogan playing Hades as a cross between Ozzy Osbourne and a biker dude. He is one of the few in a roster of fairly well-known actors who seems not only to be slumming but also sincerely depicting a character. (If you don’t know Coogan, rent Michael Winterbottom’s take on Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, A Cock and Bull Story.)

The same can’t be said for Uma Thurman, who makes no attempt at sincerity and simply has a blast. Her Medusa is almost worth the trip to the movie. Wearing a black leather coat with a collar to die for (or turn to stone for), and channels a spa denizen gone to the dark side. And even a head-full of snakes doesn’t overshadow her performance.

Percy Jackson and The Olympians will never, ever be on anybody’s list (except the Razzies?) of top movies. But it does leave us with an abiding mystery. Why, of all the Greek gods depicted on screen, including Melina Kanakaredes as Athena, is Rosario Dawson’s Persephone the only one who speaks Greek? “Go away,” she says, to the Hell Hounds in Hades. Would that we could do the same.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

Poems for Valentine's Day

@Harold Davis

It's not all roses and rainbows at the Times, though. They interestingly offer Matthew Arnold's "Dover Beach" (read by Romola Garai), a poem tinged with anxiety over the coming of a modern and faithless age, in which "ignorant armies clash by night". "Ah, love, let us be true to one another," Arnold says. But it's not easy. For this new world "Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light/Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain." Would you like a chocolate strawberry with that?

And Rosamund Pike is assigned as dark a pair of love poems as anyone could choose: Rupert Brooke's "Oh! Death Will Find Me" and Christina Rossetti's "Remember"--both works trying to assert love's permanence in the face of the inevitable.

Of course that's how it is with the best love poetry. It never loses sight of the inherent folly of romance.

Take a tour through what The Poetry Archive has to offer--and go to their website, where more recordings are available. For contemporary American poetry, visit Poetry Speaks.

What's your favorite Valentine's Day poem? And is it satirical or sincere?

Monday, February 8, 2010

Children's Books

It’s a great line. Subtly British with its “oy”, collegial (it’s “our” train), and just feisty enough to signal that something exciting is about to happen. The book of that title sits somewhere on a shelf in my basement (I hope), set aside in a small pile of favorite volumes I read to my son and daughter when they were small. The son turned twenty-one in the wee hours of today, so I find myself thinking back to the stories—and specifically the phrases—that have become a part of our family language over the last two decades.

For me, besides the “oy” of John Burningham’s book, there’s A.A. Milne’s “Bisy Backson”, the cryptic phrase that so puzzled Pooh when, unknown to him, Christopher Robin headed off to school each day. Who was this Backson, Pooh needed to know? And why was he keeping Christopher Robin so busy? It’s a handy phrase, when you want to tell someone you’re going out to do errands but you’ll be home in time to get to the soccer game, or the office. Busy Backson. Speaks volumes.

Bendamalina. I can remember nothing from that book except the cadence in which I used to read its comic formula aloud. “Bendamalina, Bendamalina, go home and tell your sisters to put the soup on to heat.” And Bendamalina, because she was wearing a pot on her head (of course), would hear it all wrong. A perfect analogy to a child’s occasional bewilderment in the world of grownup language—and to my own, as a non-native English speaker occasionally foiled by idioms.

And finally: “Ooh, said all the little crocodiles.” Bill and Pete Go Down the Nile. Not exactly a classic, but somehow ever-present in my family vocabulary. When the twenty-one-year-old son shows me his diploma in a couple of years, I’m likely to exclaim “ooh”—and to follow it with a reference to those crocodiles.

Writers and readers are always being asked about their favorite book. What about your favorite children’s book? Which books stuck in your head? What were the stories from your childhood or your children’s childhood whose language became part of your very own?

Happy Birthday, Eoin!

Monday, February 1, 2010

Movie Review: Up in the Air

But the real tone of the movie is signaled right from the start by the chicly retro credit sequence. We’re in the twenty-first century—by way of the fifties.

Everything in Up in the Air tends towards marriage. That’s the movie’s prime law of physics: all bodies in motion tend to hope for married life. Some of that we expect. We expect that Anna Kendrick’s young trainee will voice the earnest rebuttal to Clooney’s soulless philosophy. We expect that Clooney’s life will be shown up for its emptiness. We expect him to have A Revelation that he wants more out of life. We even expect that there will be a twist involving his relationship with Vera Farmiga’s equally rootless and commitment-free Alex.

What we don’t expect (stop reading here if you don’t want to know) is that the surprise is not that the woman is just as much a player as the man. Jason Reitman is not going for a gender commentary here. Instead, he’s going for an affirmation that marriage is the correct state in which people should live. That’s what Kendrick’s Natalie wants, that’s what Alex has (it’s not another man in her bed, but the even more scandalous husband in the kitchen that provides the movie’s final frisson), and that’s what Clooney’s stranded Ryan Bingham wants.

In the end, though, Up in the Air is cleverly just what its title says. In the final sequence, we see Clooney standing in front of a giant departures board. We know from an earlier scene between him and Farmiga that the board is where you go when you can choose to go anywhere in the world. You just take your frequent flier miles and pick a city. Now Clooney stands with the names of cities behind him and an exit sign directly above his head. Off he goes. But it’s a Sartrian huis clos. There’s really no way out.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

B-Movie Classics

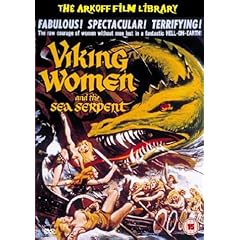

Ever heard of the Roger Corman classic The Saga of the Viking Women? Would you recognize it if I gave you its full title: The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent? Not ringing any bells? Well, maybe it will after you've had a chance to view it for free at BMC, a website dedicated to B-movie classics.

That's where you'll find about thirty gems of second-rate cinema, categorized by genre for easy searching (though versatile B-films like Saga show amazing crossover ability, turning up in both the Sci-Fi/Fantasy and Action/Adventure categories).

I owe it to the clever people at the New York Observer's Very Short List for alerting me to BMC. The Observer's List is indeed Very Short: one item every day, sent by email newsletter to subscribers. Sometimes it's a book you'll want to read, sometimes it's a website worth checking out (the guy who speaks Dadaist paragraphs in his sleep; the photographer whose black-and-whites of starling flocks rival anything Hitchcock could do). It's almost always worth taking a look at. Just like BMC's movies. Like Fiend Without a Face. Or The Crawling Eye. Or Wet Asphalt. You get the picture.

Monday, January 25, 2010

Movie Review: A Single Man

Ford lets his camera occupy two extremes: it’s either immobile or incessantly mobile. We’re either staring at an eye or a nose in super-tight close-up, or we’re jumping around in quick-cutting shots, skipping seconds here and there in what would otherwise be a straightforward sequence. Or we’re panning across a scene in super slow motion. Or we’re shifting into a quasi-handheld mode as we follow Colin Firth’s George Falconer through his day as he grieves for the loss of his lover of sixteen years. This is all very well, and demonstrates Ford’s willingness to experiment with the many things a moving image can do. But it leaves the viewer with a sense of incoherence. Yes, George Falconer is struggling, and let’s just say (without giving anything away) that time’s passing is important to him. All the same, Ford’s camerawork has the unwanted effect of making the moviegoer frequently check her or his watch.

Really, A Single Man is many movies. It’s a highly saturated 60s reverie. It’s a black-and-white magazine ad for Calvin Klein Eternity (see the movie and you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about). It’s yet another entry in the architecture-porn category, this time leading us to marvel at the pay scale of English professors at second-rate Santa Monica colleges. A Single Man is also an expressionistic tone poem, a satire, an homage to Life magazine. You get the picture.

Thankfully, it’s Colin Firth who makes the picture. Not only does he look good in twentieth-century clothes, but he gets a chance to demonstrate an enormous range of emotions all in one performance—without at all making us think he’s showing off. It’s a testament to the power of Firth’s acting that his George does not get lost in Ford’s camera flourishes. Where the camera is often extremely heavy-handed, Firth is subtle and restrained. Ford gives him a slow-motion panning shot of his own at one point. But Firth doesn’t need a camera trick to command our attention.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Guest Blogger Part Two: Tarantino and Peckinpah, Auteurs of Revenge Violence

Pupil Tarantino tweaks Peckinpahís vision of revenge ethics so that dilemmas are never black and white. Tarantinoís rogue characters operate in a contemporized moral gray area. In his first movie, Reservoir Dogs, a band of robbers is hired by a third party to pull a heist.

After the robbery, the band meets in an abandoned L.A. warehouse where each character introduces personal codes that fuel his behavior. For example, Michael Madsonís Mr. Blonde likes to torture cops, and Harvey Keitelís Mr. White is an old-school criminal in it for the money. Mr. White also has a gooey moral center that does him in by the end when he discovers the robber heís been protecting turns out to be an undercover cop.

In Pulp Fiction's moral universe, Butch the fighter (Bruce Willis), through a series of random events, helps his nemesis, Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames), out of a tight spot. Butch and Marsellus are tied together by double-cross and revenge: Butch was paid to throw a fight which he did not. Marsellus lost big money and wants Butch gone. Saving Marsellusí from the clutches of a couple of L.A. racists will more than square Butch. Butch is generally honorable, so watching him liberate Marsellus is entertaining and satisfying.

In Kill Bill 1 and 2, Tarantino serves revenge as the main course, and turns in over three hours of Uma Thurman's wronged Bride as an ass-kicking samurai warrioress bent on completing the titular task. Itís almost a let down when Bill is finally killed with a low-key martial arts blowótame compared to the mayhem that precedes it.

With Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino revises WWII for a new generation, this time as a revenge-fueled fantasy pitting American and French Jews against Nazis in German-occupied France. Audiences gave two thumbs up to the movieís hard R-rated violence, perhaps suggesting Americans are collectively tired of fighting unwinnable wars and amorphous foes. Maybe we want to relive Americaís last genuine win.

The opening scene of Inglourious Basterds extends for about 20 minutes. Presented in real-time, the scene sets up many things: weíre in Nazi-occupied France and are in the company of feared Nazi Colonel Hans Landa, nicknamed the Jew Hunter. During an extended dialogue scene in a farmhouse where he sweats a farmer for information, Landa determines that the cellar below them is the hiding place of a Jewish family. When German soldiers kill the family, a girl escapes.

This sets up what must be the most outrageous revenge fantasy ever filmed. Tarantino revises history to suit his purposes of conflict, tension, and revenge. Seeing a theater-full of Nazis, including Hitler, Goering, and Goebbels, die at the end of the movie was a little bit of heaven on a rainy September afternoon. For decades the Holocaust has been the subject of movies that were sometimes of questionable taste. Finally a filmmaker cuts to the chase and shows us what audiences have wanted all along.

Where does violence in movies go from here? What else is there for these aging outsider anti-heroes and their directors to do? Peckinpah, for his part, tackled oncoming old age by asking the macho old-man question: how do you grow old without getting done in by modern ways? The essence of Peckinpahís aging moral outrage can be reduced to a moment, a sentence, when during The Wild Bunchís opening bank robbery William Holden shouts to one of his Bunch: ìIf they move, kill ëem.î

Tarantino, now in his mid-to-late 40s, shows no sign of changing gears. As he said in the August 2009 GQ, he has already made his character-driven, mature work about getting old, Jackie Brown. ìAnd itís as much of an old-man movie as I ever want to make.î Tarantino will eventually pass the torch to another generation of revenge-violence filmmakers, but it sounds like heís not going quietly out without a cinematic fight.

The opening bank robbery from The Wild Bunch:

Need more? To see an 30-second distillation of Reservoir Dogs performed by animated bunnies, click here.

Monday, January 18, 2010

Guest Blogger: Tarantino and Peckinpah, Auteurs of Revenge Violence, Part 1

Watching onscreen violence can be a release, a harmless thrill; we watch murder most vile so we wonít actually perform the acts ourselves. Today, PG-13 movies show blood-soaked bullet holes and hungry vampires/zombies in action. And America loves it.

Quentin Tarantinoís Inglourious Basterds which includes scenes of intense violence was on many criticsí 2009 top ten lists. The January 8th issue of Entertainment Weekly chose the movie as an expected Best Picture Oscar contender. Reviews skewed mostly to the B, B+, A- range. While itís not the best movie of last year, it is certainly one of the most entertaining ones. And itís not just critics who think so: the movie is now Tarantinoís biggest box office hit.

Most of Tarantinoís movies exploit violence, and especially violent revenge, for entertainment. But years before Tarantino watched his first exploitation flick, director Sam Peckinpah released a string of visceral action movies, starting with The Wild Bunch in 1968, which helped usher in a new generation of movies that didnít have to shy away from realistic gunplay. In The Wild Bunch, and later with The Getaway and Strawdogs, Peckinpah staged action scenes as an extended slo-mo catharsis of revenge-fueled violence.

His movies donít just build to a violent ending; they start violently and continue relentlessly until the bloody finale. Peckinpahís anti-heroes live by an ethical code of conduct that ultimately places them in deadly confrontations whose outcomes are certain death. But the protagonists continue in the face of incredible odds because they know they are doing the right thing within the construct of their world view. For Peckinpah, codes are often forged from money, friendship, and revenge, forking into sub-code tributaries like honor, pride, and shared history.

His scenes of violence cultivate a universal feeling of us-against-them. The aging gang at the heart of The Wild Bunch is screwed by a Mexican general when he kills a member of the Bunch after promising to let him go. In turn, they kill the general in his compound and go down in a blaze of guts and glory. The Bunch knew their way of operating was displaced in the new west and would probably get them killed. Why not go on their terms?

Peckinpah was always attracted to outsiders and what happens when theyíre double-crossed. As David Thompson says in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, ìThroughout Peckinpahís work, there is the theme of violently talented men hired for a job that is loaded with compromise, corruption, and double-cross. They strive to perform with honor, before recognizing the inevitable logic of self-destruction.î

The Getaway starts with Steve McQueen as Doc McCoy leading a dangerous a bank heist. When heís double-crossed, the movie continues as a chase movie, ending with a brutal, inevitable shootout in the hallways, stairwells, and elevators of a Mexican border town hotel. We know whatís coming, the movie telegraphs it an hour beforehand.

But this foreshadowing ramps up the conflict and tension leading to McCoyís final retribution. Peckinpah is a master at building tension. Even after a dozen viewings I still get a jolt when I pop in The Wild Bunch. The title sequence alone is textbook Peckinpah: cross-cutting between the interior and exterior of a bank during a daring robbery.

Tune in next time as we discuss Tarantino's films, and how he has updated revenge violence for a contemporary audience.

Meanwhile, check out this trailer for Peckinpah's Strawdogs:

Come back on Thursday for Part 2!

Saturday, January 16, 2010

Coming this week: Guest Blogger Dell Smith

Dell's posts will come hot on the heels of Malcolm Jones' recent Newsweek article about what Hitchcock's Psycho did for violence and horror in American films.

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Movie Review: Sherlock Holmes

I confess ignorance regarding what crimes the Freemasons may have committed against either Ron Howard or John Turtletaub. But for why they turn up in Sherlock Holmes, I may have an answer.

You don’t have to have read “A Study in Scarlet” or “The Sign of Four” to know that Holmes can identify a man’s profession, his physical condition, and what he had for dinner simply by looking at his hands or the hem of his trousers. (Reading Conan Doyle provides a clear and unapologetic window on Victorian culture. Prejudices and stereotypes are vividly drawn in Conan Doyle’s character descriptions.) That’s one of the many fascinations of a Conan Doyle story. The world may be full of mysteries—one per story—but it is eminently solvable. The answers are all there in code, and Holmes has the key.

But for better or for worse, our world offers no such certainties. A man with a thick neck could be a brick-layer or a professor who works out a lot. So if you’re recasting Victorian Holmes for the twenty-first century, you need to find something the audience can recognize as both familiar and mysterious. Voila the Freemasons! They come with pentagrams and triangles and eyeballs and crosses, and we can watch as Holmes draws patterns on a dusty floor and points out how the pieces all fit. Freemasons! An ancient order here to solve your modern-day movie woes!

And if following along with the Masonic symbols doesn’t work, you can always trace the semiotics of Robert Downey Jr.’s hair. Tousled, smooth, beneath a fedora. What does it all mean?

Monday, January 11, 2010

Call Me Curious: the Moby Dick Marathon

It’s not that I’m a particular fan of Moby Dick. I neither liked nor understood the book when it was assigned in high school. But the chance to witness such an extreme combination of literature, performance, and endurance was too intriguing to pass up. I imagined it as a literary do-over of They Shoot Horses Don’t They, with readers staggering up to the podium, slurring their words after hours on their feet. I figured the museum’s reading room would look like the sidewalk after a camp-out for Coldplay tickets, littered with food wrappers and sleeping bags and coffee cups.

No such luck. The Whaling Museum is a modern building tucked among the colonial houses of the old city, and the atrium lobby where the reading marathon took place was sleek and full of light from the enormous windows along the back. No one was having trouble staying awake. Three whale skeletons hung from the ceiling above a space divided into two sections: readers to the right, spectators to the left. I found a place on the stairs down to the lobby, on the readers side, but nobody sent me away.

Everyone had a copy of Moby Dick, some loaned by the museum, but most looking like much-loved and much-read volumes pulled from home shelves. Barnes and Noble was there, offering nooks on loan. Here was a fusion of the very old and the very latest: a nineteenth-century classic, available in digital form, read aloud by people from Melville’s very own part of the world. Interestingly, virtually everyone was following the spoken reading along in their books. I didn’t have a copy, so I simply listened, which seemed to me to be the point.

I heard a woman read not as distinctly as I would have liked, a man read with lovely theatrical aplomb, a woman read in Portuguese—in which the few words I understood included “Ahab,” “Pequod,” and “melancolia”—and then just before I had to leave, the actual great-great-grandson of Melville himself. A tall man with glasses and a short gray pony tail, he had the privilege of reciting the moment when Moby Dick bites the whaling boat in two. I’m guessing he gets to pick his favorite part.

Who goes to an event like this? Mostly people with gray hair, mostly people wearing LL Bean-type clothes. But also a young man in skinny jeans and a deerstalker; a kid in a Marblehead Badminton t-shirt; and a handful of grad-student types who must have been there in homage to Melville, the post-structuralist. What I expected to see more of I saw only one of: a man in work pants and Jason Bourne’s red down jacket, with a watch cap and mutton-chops. A sailor.

Maybe Melville isn’t your favorite book. Maybe twenty-five hours of recitation isn’t your idea of fun. But there’s something to be said for sitting in a room beneath the bones of a whale, listening to people say things like “There she blows!”

Thursday, January 7, 2010

Curling up With a Good Audiobook

Monday, January 4, 2010

Z (1969)

Z: a perfect place to start the New Year. Why the last letter of the alphabet? Because it’s also the sound (zee) of the Greek word for “he lives”, a cry of new or renewed life. This doubling of meaning is exactly what Greek filmmaker Costa-Gavras had in mind when he gave his 1969 political thriller this famous one-letter title.

Z follows the return to an unnamed country of a political leader known only as the Deputy (Yves Montand). As his entourage arranges for him to address his supporters on the topic of peace and freedom, an opposing mob gathers and threatens to kill him. One man clubs the Deputy in the head, sending him into a coma, and sending a range of authorities into action. The doctors analyze his still-living brain; the Magistrate examines the case; the rulers obfuscate; and the crowds riot. Once the Deputy is dead, his supporters insist that he and his cause still live. “Zei”, they cry, speaking the only Greek word in the movie.

Z was filmed in Algeria and acted in French, with Irene Pappas as the Deputy’s wife standing out as the lone and noticeably Greek figure among the cast. (Pappas’s ethnicity is hard to mistake: she has the dark eyebrows and hair and the long straight nose of a classical statue. When she played Clytemnestra in Michael Kakoyannis’ 1977 film Iphigenia, it was like looking at the ancient queen come to life.) Z could never have been made in Greece. Two years into what would be the seven-year rule of a military junta, Costa-Gavras’ overt criticism of the police state would have been extremely dangerous.

Besides that one word cried out by the Deputy’s supporters, the only signs that the film is a thinly veiled reference to the junta are clever glances at Greek lettering here and there. Pappas holds a copy of Ta Nea (The News), the left-leaning newspaper. Medals shown in the beginning of the film are from Greek campaigns. And, most appropriately, a close-up of a reporter’s Selectric typewriter ball shows Greek characters, with the Z popping up front and center. But everything else, from the dark-glasses-wearing leader of the police state, to the murkiness of due process, to the reaction of the mob, rings utterly and explicitly true of Greece.

I saw Z in mid-December, and applauded Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts for picking that moment to screen a film about Greece’s struggle between anarchy, independence, and authoritarian rule. Z is full of scenes of police standing by while mobs threaten to take over, and then entering the fray too late and too forcefully. How prescient of the MFA to synchronize Costa-Gavras’ film with riots going on in Athens and other major Greek cities during most of December 2009. Or was it?

The sad truth is that riots in Greece—between a mob that rejects the very notion of authority and a policing force that doesn’t know how to assert authority without oppressing—these riots have become an unremarkable occurrence in Greek life. The MFA’s scheduling was pure luck; they could screen Z any day of the year and it would be timely. Costa-Gavras’ film has had a much longer life than perhaps he could have hoped for—and for, sadly, all the wrong reasons.